だいちの星座について

鈴木浩之[金沢美術工芸大学 准教授]

画家が画面上に描く点は、最もシンプルな造形の一要素と捉えることができる。一方で絵画上の点を幾何学的に定義することは困難とする考え方もある。だいちの星座プロジェクト代表で絵画制作技術についての研究が専門の鈴木浩之は、絵画における点が〈形〉〈面積〉〈材料〉を切り離して考察することのできない複雑な要素だと考える画家の1人である。本活動で鈴木は、絵画上の点について深く知る為の手段として、より大きなスケールで絵画制作を行うことで芸術における点が集中と緊張を伴う複雑で強い〈作家の意志〉の表れであることを(その制作のプロセスや結果として現れる大きな〈点〉の痕跡によって)明らかにしようと試みた。

抽象絵画の祖として知られる画家のカンディンスキーはその著書『点と線から面へ』の中で、芸術における点が数学における点とは異なり「1.(大きさと形の)集合体であり、2.輪郭のはっきりした統一体……」(Kandinsky,1926 宮島訳, 1995, p.29)と述べている。同書の点に関する考察は絵画の分野に留まらず建築や彫刻、写真、音楽、など多岐にわたり、芸術にとって点が位置を定める機能に加え、ベクトルやゾーンを示す余地を内包することについて触れている。点について知るために、これまでに描かれてきた絵画を顕微鏡で拡大するようにして分析していくことも方法のひとつであろう。一方で鈴木は離れた位置から見なければならない大きな絵画の制作を行うことで分析が可能となる点の機能についての多くの知見が得られると考えた。

高高度の視点で広いエリアを捉え、レーダと電波反射器を利用して地上に「星」を描く《だいちの星座》の活動は、鈴木が2010年度文化庁メディア芸術クリエイター育成支援事業の採択を受けて実施した「人工衛星を利用した地上絵の制作研究」を経て、2013年より宇宙航空研究開発機構(JAXA)の大木真人と共にスタートさせた共同研究に基づいている。本活動で描く「星座」を構成する「星」は、地上で反射した電波の点描〈絵〉である。

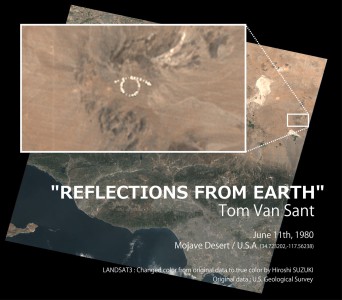

ロバート・スミッソンの描いた《スパイラル・ジェティー》を、肉眼で空から見降ろすことができる機会は多くの人に与えられるわけではなく、一般的にはドキュメント映像や写真、現地の地上からその規模や形状を認識するところが大きい。1980年に人工衛星の利用を意図した初めての地上絵《リフレクションズ・フロム・アース》の制作がトム・ヴァン=サントによってアメリカ、ロサンゼルス郊外のモハーベ砂漠で実施され(坂根, 2010, p.310)、鏡による太陽光の反射を利用して描かれた地上絵が地球観測衛星「LANDSAT-3」の観測データに記録された。この時記録された(人の「眼」が描かれている)地上絵は、地表を均一に観測する目的から撮影された地球観測データの一部として(これまでに人類が得た地球外の視点による地球観測データと同様にそのほとんどが)アーカイブされている。1989年にはピエル・コントゥがフランスで《シニャチュール・テール》を制作し地球観測衛星「SPOT-1」がこれを撮影している。(鈴木, 2013, p.72)これらの作品の記録を含む人工衛星画像は現在でもそれぞれの地球観測データを管理する団体から(有償、もしくは無償で)ダウンロード可能で、今後とも同様の形態により各国予算によって継続して保存される可能性が高い。人工衛星による地球観測システムは、今日、既に芸術作品制作における記録メディアとして機能している。

定点観測

萩原朔美氏は「だいちの星座 -たねがしま座・つくば座・もりや座-」展の関連企画シンポジウム(2015年8月/本書p.102を参照)の中で、「『だいちの星座』は定点観測によって浮かび上がる日常生活の中の特異性を見ようとする作品だ」と指摘している。本活動は人工衛星によって定点観測の視点を得ている。作品中に「星」として描き出した無数の点は、定点観測と差分解析によって人工衛星画像から浮かび上がる日常生活の中の変化を表している。ここでは《だいちの星座》と定点観測の関係について触れたい。

地球観測衛星は(ほぼ)同じ高度と軌道から地球を観測し、同じエリアの画像を繰り返し撮影することで定点観測を行う。利用者はこれらのデータから地球上の様々な変化を見つける。高度な科学の集積と理論を具体化するテクノロジーによって常に正確な運用が行われる人工衛星を利用することで、現代に生きる私たちは宇宙から地球を見る定点観測の視点を得ることができる。日本の地球観測衛星のひとつである「だいち2号」もまた、私たちに定点観測の視点を与える。「だいち2号」に搭載されているセンサは、自らが地上に向けて発信した電波を再び受信することで地球を観測する。その電波は雲を透過する性質を持つために、どんな気象条件の下であっても地上を観測できる可能性が高く、地形の調査や土地被覆に関する定点観測に適しているとされる。

《だいちの星座》は人工衛星による定点観測から得られる衛星画像を芸術作品制作に利用する。人々の日常の中に起こる変化が、実は繰り返すことのできない特異の連続であり稀な出来事であることを表そうとした時、鈴木は宇宙からの定点観測を利用しようと考えた。鈴木と大木は撮影のタイミングが異なる2枚の衛星画像(撮影エリアは同一)を重ね合わせ、同じ位置同士であっても撮影のタイミングによって変化が生じている箇所を抽出することで第3の画像を描き出す。実際に地上を観測して得られた2枚の画像とは異なるこの第3の画像上には、海岸線や山の尾根、立ち並ぶビルや大きな鉄塔等の普段はあまり大きな変化が生じない形は消え、海に浮かぶ大きな船や信号待ちをするトラック、森の中で伐採された大きな木や町の中に建てられた新しい家など、日常の中で変化していく大きな形が無数の点となって出現する。鈴木らは第3の画像に現れるこれらの点を大地に描かれた「星」と見なし、参加者らが手作りの電波反射器を製作・配置して地上に新たに「1等星」を描き加えることで《だいちの星座》を完成させる。このように、《だいちの星座》は人工衛星が提供する定点観測の機能を利用して、その地域に住む人々の生活の痕跡を無数の星に見立てて可視化してきた。大地に意図的に「星座」を描く活動と、その地域に住む人々がそれぞれの生活によって描き出す無数の「星」が重なることで《だいちの星座》がつくられている。

だいちの星座の星が表す意味

《だいちの星座》に描かれた「星」の多くは日常の痕跡である。それらの「星」は自然現象によって変化したものに加え、人々が生きた証(新築の家、港に運び込まれたコンテナ、採石場、材木の切出し、等)として人工衛星画像に刻まれたものも少なくない。《だいちの星座》は「だいち2号」が撮影した人工衛星画像に記録されている人々の日常を振り返る機能があると言い換えることもできる。

人の日常の痕跡は私たちに何を伝えるだろうか。《だいちの星座》の作品上では、記録された時期が異なるある地点の(形状変化による)電波反射角度や散乱特性の変化が「星」の輝きになって表れる。鑑賞者は、日々繰り返されていると感じる日常の風景の中に〈異なる瞬間の連続〉を見つけることができるかもしれない。また《だいちの星座》の中で発見する変化に、自らが参加して描き込んだ特別な「星」があるとすれば、それらの「星」の輝きが〈人々の生活が貴重で稀な時間である〉と考える人もいるかもしれない。人々の日常が決して繰り返されることのない稀な時の連続であることを《だいちの星座》は表している。

哲学者の三木清は、人の行動を促す不安な気持ちと行動の結果として現れる〈形〉の関係性から構想力のメカニズムを探っている(三木, 1967)。人は思い悩みながら行動するうちに様々な形を地上に生み出している。〈形〉は人の思考の痕跡であり「芸術」や「科学」によって社会に明らかとなるとすれば、その〈形〉を捉える機会は既存の機材のみに委ねるべきでは無いと鈴木は考えている。地球の外から人々の生活を眺める視点を利用する現代では、人々が生み出す建築物や地形・植生の変更といった変形を高高度から容易に捉えることができるようになりつつある。写真機やフィルムカメラがその登場から早い時期に芸術表現の為の役割を与えられたように、人工衛星もまた芸術表現の為の役割を引き受け始めている。世界中の変化を広い視野で捉える地球観測システムは今後も様々な波長の電磁波を利用して地球上により多種多様な〈形〉や〈差〉を発見し、明らかにしていくことだろう。

写真としてのだいちの星座

写真の定義に光とレンズが不可欠だということであれば、完成した《だいちの星座》の作品を写真作品と呼ぶことはできない。しかし、写真の定義をより広く捉え「(可視光に加え電波を含む)電磁波を像として持続させ得るプロセス」を〈撮る〉ことだとすれば、Lバンド合成開口レーダによって撮影された人工衛星画像を元に制作した作品は写真作品である可能性がある。

《だいちの星座》を制作する元となる写真、即ち「だいち2号」の観測画像の著作者は宇宙航空研究開発機構(以下JAXA)である。2017年5月現在「だいち2号」の観測画像が公開される際には多くの場合「©JAXA」が付記される。観測画像はJAXAのデータベースで保管・管理され、プロダクトとしてシーンIDや撮影時刻・エリアなど様々な条件を指定することで検索が可能で、研究の目的に限らず、広く一般利用を可能とする民間企業による販売も行われている。《だいちの星座》の活動では「だいち2号」に参加者ら自らが製作した電波反射器を観測させるが、成功すればこの人工衛星画像にはそのときに描いた《だいちの星座》を構成する〈1等星〉が、JAXAによって恒久的にデータベースにアーカイブされることを意味している。

《だいちの星座》作品が狭義の写真作品では無かったとしても、それは従来の写真作品のフォーマットを擬態している。まずこの活動記録集そのものが「写真集」として機能することを目指しており、本書掲載の作品画像が《だいちの星座》作品そのものとして認識されることを否定しない。さらに、デジタルCプリント出力によるオリジナルプリント作品を制作している。オリジナルプリントでは〈地球外の視点による高高度からの地球観測〉や〈微弱な電磁波が地表で反射したさま〉を深い黒色で表現すると共に、芸術分野の展示における写真作品との比較を容易にしている。地上で用いるカメラと同様に、リモートセンシングによる地球観測システムが芸術作品制作に利用可能な機材であり、撮影された観測画像をコンテクストと共に鑑賞者に提示することで《だいちの星座》作品の芸術としての表現が成立することを示している。

絵画としてのだいちの星座

人が絵を描く行為には多くの場合に構想を必要とする。構想には不安が伴うと指摘した三木の考えは既に述べた。《だいちの星座》参加者の多くは、本活動とある種の不安を共有してきた。コーナ リフレクタ型の電波反射器の製作では塩化ビニル製のパイプを利用してフレームを組み立て、そこにテニスのラケットのように金網を張り、それぞれの面が90度に接するようにつなぎ合わせた構造物を完成させる。金網の張り具合やつなぎ合わせる面を90度に保つことは、電波の反射に影響することを承知する参加者にとって不安を伴う行為である。くわえて、完成した電波反射器を学校のグラウンドや公園などに配置する際には、電波反射器を正しい方角に合わせる必要があり緊張を伴う。そればかりか、「だいち2号」が災害等の発生による緊急の事態によって当初予定されていたエリアとは異なる対象を撮影することも考えられ、観測される確率は100%ではない。

参加者らは鈴木や大木らと共に、多くの不安を乗り越えて《だいちの星座》を完成させる。参加者らにとって《だいちの星座》は自らが描いた絵である。参加者は完成した作品としての《だいちの星座》を特別な観点で見ることになる。鈴木は絵画におけるキャンヴァス上に塗られた絵の具を〈構想の痕跡とその集積〉と捉え、身の回りの壁や床に残された様々な痕跡を見ることと絵画を見ることとの共通点について考察した(鈴木, 2000)。同書では、絵画の成立には鑑賞者が絵を見ようとする意志が重要だとし、鑑賞者に先立ち絵画制作者が自らの絵をどのように描こうとし、また、見ようとしたのかについて述べている。身の回りの〈跡〉はそのほとんどが日常において気にされることは無い。しかし、一旦その〈跡〉を見ようと注視すれば、その〈跡〉がどの様な経緯でそこに痕跡として定着したのかを類推する時間が流れはじめる。鈴木は同書で、絵画の価値が〈描く行為〉そのものにウェイトがあり、作品はその行為があったことの証拠物として捉えることができると述べている。《だいちの星座》の作品もまた、考察の断片(の写真)だと言える。

《だいちの星座》が、人々が大地に絵を描こうとした行為であることは、作品の外形からは伝える術がない。人工衛星を利用した芸術作品制作が一般化していない現状において、参加者以外の鑑賞者が《だいちの星座》の作品を見るには、ある程度のテキストや地上での活動を紹介した写真、または電波反射器、人工衛星の模型を併せて展示することが有効だと、本活動は考えている。地球と人ひとりを直接結ぶ新たな社会認識の方法を提供しようと試みる本活動は、《だいちの星座》の展示において、電波反射器の配置場所で確かに人工衛星に向けて電波を反射させたという証拠物を開示することで、地上絵のグラフィックがつくられた現場を鑑賞者に想像させようとしている。

数学の〈点〉、芸術の〈点〉、だいちの星座の〈点〉

ユークリッド原論的な理解によれば、点には位置があるが部分は無いとされる。一方で、鈴木らは《だいちの星座》の活動で地上に多くの点を描いてきたが、それらの点は〈それ以上細かく分けて使わないもの〉または〈長さや重さ、体積を持たない位置〉といった数学的な意味に限定されない。《だいちの星座》で描かれた点をよく見ると四角形や十字形、流星形など様々な形を発見することができ、描かれた点には部分があると言える。

芸術における点は、美術分野においては筆の先で描かれたキャンヴァス上の絵の具、音楽分野においては五線譜の音符にも見ることができる。キャンヴァス上の絵の具を拡大して見れば、そこに色の広がる面積と形に加え、厚みや光の反射など様々な〈部分〉を見ることが可能で、音符で指示された音階を複数の楽器で鳴らすと空気の振動の仕方が異なる様々な音色が聞こえ、やはり音符にも〈部分〉が隠れていることがわかる。

従来、芸術における点とは局所的な事象を指す便宜的な呼称であったように思われる。ある絵画上の点は青く渦巻く不穏な夜空を構成し、ある映画では1発の銃声が全体を支配した。点と認識されてきた作品内の局所的な事象は、人の感性が基準となっていることが多く、点として言語化しようとするその先には言語化が困難なほど微細な面積や形、伝搬する空気の振動等の変化が複雑に重なった世界が続いている。

大規模な地上絵制作において描かれる点の特異性を観察することで得られる知見は、キャンヴァス上に描かれた点や音符が奏でられる瞬間に何が起こっているのかの発見を促す。《だいちの星座》で描かれた「星」は、地上に配置した幾つもの電波反射器が反射させた電波が人工衛星に届くことで観測されたもので、〈部分〉の集合だ。人工衛星からの電波を受信する20秒ほどの時間を共有する体験もまた、電波反射器の角度を合わせ続けようとする緊張した瞬間の集合であり、複雑なプロセスが絡み合っている。《だいちの星座》は「星座」を構成する一つひとつの「星」(=点)の下に、多くの部分と瞬間が詰まっていることを知る経験でもある。

《だいちの星座》は宇宙に浮かぶ地球の上に〈人〉を一つの点として輝かせることもできる。地上絵の構想が広場に人を集め、人工衛星の機能によってその活動の時間と位置が記録される。定点観測を可能とする質の高いシーケンスを提供した科学と、それぞれの地域において繰り返すことのできない稀な瞬間を閉じ込めようとした芸術とが、同じフィールドで描いた点の集積、それが《だいちの星座》の点である。

<参考>

● ヴァシリー・カンディンスキー(宮島久雄訳)(1995)『点と線から面へ』(バウハウス叢書9)中央公論美術出版

● 坂根巌夫(2010)『メディア・アート創世記 科学と芸術の出会い』工作舎

● 鈴木浩之(2013)「宇宙芸術の変遷~人工衛星を中心として~」金沢美術工芸大学『金沢美術工芸大学紀要』57:69-77

● 三木清(1967)『三木清全集 第8巻』岩波書店

● 鈴木浩之(2000)『跡の概念と美』鈴木浩之

On Constellations of the Earth

Hiroshi Suzuki

Points drawn on a surface by painters can be thought of as the simplest element in the figurative arts. Some believe, however, that points in pictorial art are difficult to define in geometrical terms. Hiroshi Suzuki, who heads the Constellations of the Earth project, specializes in research on techniques for producing pictorial art, and he is one among painters who believe that points in such art are a complex element that cannot be discussed without consideration of shape, area and material. In this project, Suzuki produces pictures on a large scale as a way to gain a deeper understanding of points in pictorial art. By doing so, he seeks to illustrate (through the large markings, the points, that emerge in the process of, or as a result of, this production) that points are a strong, complex expression of the artist’s will that is imbued with focus and tension.

Kandinsky, who is known as the forefather of abstract painting, wrote in his Point and Line to Plane that points in art differ from those in mathematics in that they are “1. a complex (size and form) and 2. a sharply-defined unit” (Kandinsky, 1979. p.35). The observations on points in the said work are not limited to the field of painting, but rather cover a wide range from architecture to sculpture, from photography to music. Kandinsky remarks that in art, a point not only serves to determine positions, but also has the capacity to indicate vectors or zones. One way to go about learning more about points might be to analyze past paintings as if by magnifying them using a microscope. Suzuki, however, reasoned that producing large pictures, which would have to be seen from a distance, would enable analysis that would yield great insight into the characteristics of points.

Suzuki’s Constellations of the Earth draws pictures on the ground using radars and corner reflectors, capturing a large area of land from a high altitude. The project was founded on his research on creating geoglyphs using satellites, which he carried out as the 2010 selectee for the “Project to Support the Nurturing of Media Arts Creators” run by the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and on his subsequent collaborative research with Masato Ohki from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), which they initiated together in 2013. The constellations in this project are “pointillistic” pictures formed by reflecting radio waves at points across the land.

Few are afforded the opportunity to view Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty from the sky with their own eyes. Its scale and form are largely perceived through documentary footage or photography, or on the ground at the actual site. In 1980, Tom Van Sant produced Reflections from Earth, the first-ever geoglyph to utilize an artificial satellite, in the Mojave Desert outside Los Angeles, U.S.A. (Sakane, 2010. p.310). The picture, created by using mirrors to reflect sunlight, was recorded in the data collected by the Earth observation satellite LANDSAT-3. The recorded geoglyph (which depicted a human eye) has been archived – along with most data on Earth that mankind has hitherto gathered from outer space – as part of the data taken for the purpose of uniformly observing the Earth’s surface. In 1989, Pierre Comte created Signature Terre, which was captured by the Earth observation satellite SPOT-1 (Suzuki, 2013. p.72). The satellite images that record these works are still available today on download, for a fee or gratis, from the organizations that administer the relevant data. It is likely that such data will continue to be preserved in a similar form, funded by national budgets. Earth observation systems using satellites already serve in today’s world as a recording medium for artistic creations.

Fixed-point observation

At the symposium held in connection with the exhibition Constellations of the Earth: The Tanegashima, Tsukuba and Moriya Constellations (August 2015; see p.104), Sakumi Hagiwara commented that “Constellations of the Earth is a work that seeks to find singularity within everyday life through fixed-point observation.” This project uses artificial satellites to secure a viewpoint for fixed-point observation. The countless points drawn in the works, the “stars,” show changes in everyday life that are revealed by fixed-point observation and difference analysis of satellite imagery. Here, let us address the relationship between the activities of Constellations of the Earth and fixed-point observation.

Earth observation satellites carry out fixed-point observation by monitoring the Earth from (roughly) the same altitude and orbit path, periodically capturing images of the same areas. Users can then find various changes on Earth from this data. Through these artificial satellites, which are operated with constant precision by using technology that puts a wealth of science and theory into action, in today’s world we can secure a viewpoint for fixed-point observation that sees the Earth from outer space. In like manner, Daichi 2, one of Japan’s Earth observation satellites, provides us with a viewpoint from which to conduct fixed-point observation. The sensors installed on Daichi 2 observe the Earth by transmitting radio waves towards the ground, and receiving them again. As these waves can pass through clouds, the sensors have a high chance of being able to monitor the Earth regardless of weather conditions; as such, they are suited to fixed-point observation of topography or land cover.

Constellations of the Earth uses satellite imagery gained through fixed-point observation by artificial satellites in order to create art. Looking for ways to convey that changes occurring in people’s everyday lives are in fact a sequence of singularities, of rare events, Suzuki arrived at the idea of using fixed-point observation from outer space. Suzuki and Ohki superimpose two satellite images taken at different times (but of the same area), and compose a third image by gleaning the places where change has occurred between the two images. This third image, which differs from the two images obtained through actual observation of the ground, no longer shows shapes that usually undergo little change, such as coastlines, ridgelines, rows of buildings, and transmission towers. Instead, substantial shapes that change in the course of everyday life – large ships floating in the ocean, trucks waiting at traffic lights, big trees felled in forests, newly built houses in town – emerge on the image as countless points. Imagining these points that appear on the third image as stars decking the land, Suzuki and his team finally bring the Constellations of the Earth to completion by marking new “first magnitude stars” on the ground, which are made by having the participants build and set up handmade corner reflectors. In this fashion, Constellations uses artificial satellites’ capacity for fixed-point observation, and visualizes the traces of the lives of the local residents, presenting them as myriad stars. Constellations is created by overlaying the constellation intentionally etched upon the land, onto the countless stars figured by the lives of the region’s residents.

The meaning of stars in Constellations of the Earth

The “stars” depicted in Constellations of the Earth are mostly traces of the everyday. In addition to the “stars” born of natural phenomena, there is also a large proportion that became engraved in the satellite imagery as marks left by people’s lives (new houses, freight containers shipped into ports, quarried stone, felled logs). To put it differently, Constellation allows one to look back over people’s day-to-day environment that Daichi 2 has recorded and captured in its satellite images.

What do such traces tell us? In Constellation’s images, the glimmer of the “stars” that appear are the changes in the angle of reflection (caused by changes in shape) and changes in scattering characteristics, in a particular place at different times. Viewers might be able to discover in them a sequence of different moments, in an everyday landscape that feels routine. If there is, among the changes found in Constellations, a special star that they themselves participated in drawing, then the gleam of that star might make them see everyday life for the precious and rare time that it is. Constellations shows that day-to-day living is a series of singular moments that will never be repeated.

The philosopher Kiyoshi Miki explored the mechanism of imagination by examining the relationship between the feeling of apprehension that encourages people to act, and the shape that emerges as a result of that action (Miki, 1967). Human beings generate various shapes on the Earth in the process of deliberating and fretting over their actions. In Suzuki’s view, if shape is the mark of human thought that art and science reveal to the world, then the opportunity to capture this shape should not be wholly entrusted to machines and equipment that already serve that purpose. In today’s world, we make use of viewpoints that gaze on people’s lives from outside the Earth, and it is becoming easier to capture architectural artifacts or changes in topography and vegetation from high altitudes. Just as photography and the film camera began to play a role in artistic expression soon after the technologies were introduced to the world, artificial satellites too are beginning to assume a role in artistic expression. Earth observation systems, which capture changes all over the world through a broad perspective, will continue to discover and elucidate a wide assortment of shapes and differences, using electromagnetic waves of varied wavelengths.

Constellations of the Earth as photography

If the definition of photography requires light and a lens to be involved, then the products created by this project cannot be called works of photography. However, if we define photography more broadly, as “the process of giving electromagnetic waves (i.e. including radio waves as well as visible light) a lasting form as an image,” then satellite imagery captured with an L-band synthetic aperture radar might also constitute photography.

The copyright for the original photographs from which Constellations is produced – namely the images captured by Daichi 2 – belongs to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). As of present (May 2017), release of these images from Daichi 2 is generally appended by “© JAXA.” The images observed are stored and administered in the JAXA database, and can be searched as products by specifying various conditions such as scene ID, time of imaging, and area. They are also sold by private companies, not just for research purposes, but for wide general use. The Constellations project has the Daichi 2 observe the corner reflectors created by the participants themselves. If successful, it means that satellite images containing the newly drawn “first magnitude stars” that comprise the constellation will be permanently archived in the JAXA database.

Even if Constellations of the Earth is not a work of photography in the narrow sense, it mimics the format of conventional photographic works. Firstly, this very project archive is aimed to function as a photography book, and does not object to the images in its pages being perceived as the substance of the artwork Constellations of the Earth. The project also produces original prints using digital C-type printing. The original prints represent observed images of Earth from high altitudes above the Earth, and faint reflections of electromagnetic waves on the Earth’s surface, with dark black shades, allowing easy comparison with photographic works exhibited in the field of art. This demonstrates that Earth observation systems predicated on remote sensing are just as viable an apparatus for producing art as cameras used on the ground, and that Constellations establishes itself as a work of art by presenting viewers with the captured imagery along with its context.

Constellations of the Earth as painting

Usually when people create a picture, they first need to conceive an idea. Miki’s argument that imagination comes hand in hand with unease has already been mentioned above. Many of the participants of Constellations share certain apprehensions with the project members. The radio wave reflectors (corner reflectors) are assembled by building frames out of vinyl chloride pipes, stretching wire netting across them like on tennis rackets, then joining the frames so that the faces of the structure form right angles. Adjusting the tension of the wire netting, and keeping the attached planes at right angles, are steps that cause some concern for participants who know that these steps will affect the reflection of the radio wave. Moreover, setting up the completed corner reflectors in school grounds, parks and such is a tense process, as there is a need to set the reflectors facing the right direction. What is more, there is even a possibility that Daichi 2 might target an area different from the scheduled area due to an emergency, for example a natural disaster; one cannot be 100% certain of being captured by the satellite.

Together with Suzuki, Ohki and others, the participants overcome these many worries to complete the Constellations of the Earth. For them, Constellations is a picture that they drew themselves; they see the completed artwork from a special perspective. Suzuki discussed the pigment laid on the canvas in paintings as “traces of the conception and their accumulation,” examining the similarities between looking at paintings and looking at various traces on walls or floors in our surroundings (Suzuki, 2000). The thesis posited that the will of the viewer to see the painting is key for a painting to become established as such, and discussed how a creator of a painting goes about conceiving and envisioning their own work before the viewer. Most of these traces that surround us are given no attention in everyday life. However, once we focus on seeing them, then the time thereafter is spent in reasoning how the traces came to be where they are. In the same thesis, Suzuki argued that the value of paintings lies mainly in the act of depicting, and that the work can be seen as a physical object evidencing that act. The work created by Constellations can also be said to be a fragment of this process of consideration (or a photograph thereof).

There is no way to tell from the outlook of the work that Constellations involves people drawing a picture on the land. Given that artistic production using satellites is not currently widespread, the organizers of this project believe that it would be more effective to present Constellations’images to viewers (those other than the participants) in an exhibition that includes some text, photographs documenting the on-the-ground activities, perhaps accompanied by the reflectors and a model of the satellite. This project, which seeks to provide a new way of perceiving society that connects the Earth with each individual, presents at its exhibition physical “evidence” of the waves being reflected back at the satellites at the reflectors’ locations, in order to make viewers imagine the actual sites where the graphic of the geoglyph was formed.

Points in mathematics, points in art, points in Constellations of the Earth

According to Euclid’s Elements, a point has a position but has no “part.” In contrast, the copious points that Suzuki and his team have drawn on the land as part of Constellations of the Earth are not limited to their mathematical definitions – “something which cannot be divided any further,” “a position that has no length, mass or volume,” and so on. On closer inspection, the points in Constellations are found in many shapes – rectangles, crosses, in the form of a shooting star, and so on – and the points that have been drawn can be said to “have parts.”

In the arts, points can be found in fine art as spots of paint on a canvas marked with the tip of a brush, or in music in the form of notes placed on the staff. If one views a magnified image of paint on a canvas, one can see the shape and area filled with color, as well as other “parts” like thickness and light reflection. Similarly, when a scale indicated by notes on a score is played on multiple instruments, one can hear varied tones that vibrate the air in different ways, exposing the “parts” contained in a note.

Historically, it seems that a “point” in art was merely an expedient nomenclature for a localized occurrence: points in one painting form a foreboding night sky with blue swirls; in one film, a single gunshot dominates the entire narrative. Ascription of the term “point” to these localized occurrences in artworks has generally been based on human sensibility. Behind this attempt to verbalize them as “points” lies a complex and layered world full of subtle areas, shapes, air vibrations that transmit.

The insight that can be gained by observing the particularity of the points – points that have been drawn as part of producing a large-scale geoglyph – prompts discoveries about what it is that occurs when a dot is painted on a canvas, or when a note is played. The stars of Constellations are imaged by satellites that receive waves thrown back by many reflectors set up across the land: in other words, they are an aggregate of many parts. The experience of sharing the 20 seconds or so of time while receiving the waves from the satellite is also an aggregate of tense moments spent trying to keep the angle of the reflector exact; it is a tangle of complex processes. Constellations also involves an experience of learning that the individual stars (or points) comprising the constellations are each filled with many parts and instances.

Constellations of the Earth can allow human beings to shine as a single point on the Earth as it floats in the universe. The idea of creating a geoglyph gathers people to open spaces, and the functions of the artificial satellites record the time and location of these activities. Science that provides high-quality sequences that enables fixed-point observation, and art that attempts to crystallize precious moments in each location that can never be repeated – Constellations of the Earth is an amassment of the points that these two disciplines drew together in one field.

● Kandinsky, W. (1979). Point and Line to Plane, Dover Publications.

● Sakane, I. (2010). The Origins of Media Arts, Kosakusha.

● Suzuki, H. (2013). “Uchu Geijutsu no Hensen – Jinko Eisei wo Chushin toshite” (Changes in Space Art: With a Focus on Artificial Satellites), Bulletin of Kanazawa College of Art, 57, Kanazawa College of Art. pp.69-77.

● Miki, K. (1967). Miki Kiyoshi Zenshu (The Complete Works of Kiyoshi Miki), 8, Iwanami Shoten.

● Suzuki, H. (2000). “Ato no Gainen to Bi” (The Concept and Beauty of Traces).

Comments are closed